The Art of Unagi

One item on my to-do list while I was in Japan was to visit an unagi restaurant. Unagi is delicious freshwater eel, grilled and glazed with a sweet, soy-based tare (sauce). Its rich, fatty meat is considered a delicacy in Japan—a special food for a special occasion. Since preparing eel is a complex and refined skill, unagi restaurants can be quite fancy and sophisticated. While staying in Ginza last March, I did a quick search for a highly rated unagi spot nearby and came across Ginza Yondaime Takahashiya. I booked a table for one for an evening meal. Using Tabelog, I was able to select a set menu in advance, and I opted for a grilled-and-steamed option that came to 9,800 yen (about $65).

Once I arrived at the restaurant, I immediately noticed that I was the only foreigner there. It was a rather small, high-end spot, located high up in a tall building with a view over the fancy shopping streets of Ginza. I took a seat at the counter, and a young Japanese couple sat next to me. They looked dressed up—probably out celebrating a birthday or some other special occasion. I noticed that although we were seated at the counter, we were separated from the chefs by a thick glass window. We could see them, but not interact with them. I figured the reason for this was that the grill produces quite intense smoke and sometimes an unpleasant smell, and—being a high-end restaurant—they likely didn’t want guests to end up with it on their clothes.

The Unagi Theatre

The unagi ritual began with one of the chefs coming out and showing us a live eel in a bucket. After that, the chef (the one on the right in the picture) went back into the kitchen and proceeded to kill the eel right in front of us using an incredibly precise, fast, and efficient technique.

In Japan, fish is typically killed using a traditional method known as ikejime (活け締め)—a quick and humane technique that preserves flavor and texture. When it comes to unagi, though, things are a bit different due to the eel’s slippery body, strength, and resilience—even after being cut. For that reason, eel killing and butchering is considered one of the most difficult skills in Japanese cuisine.

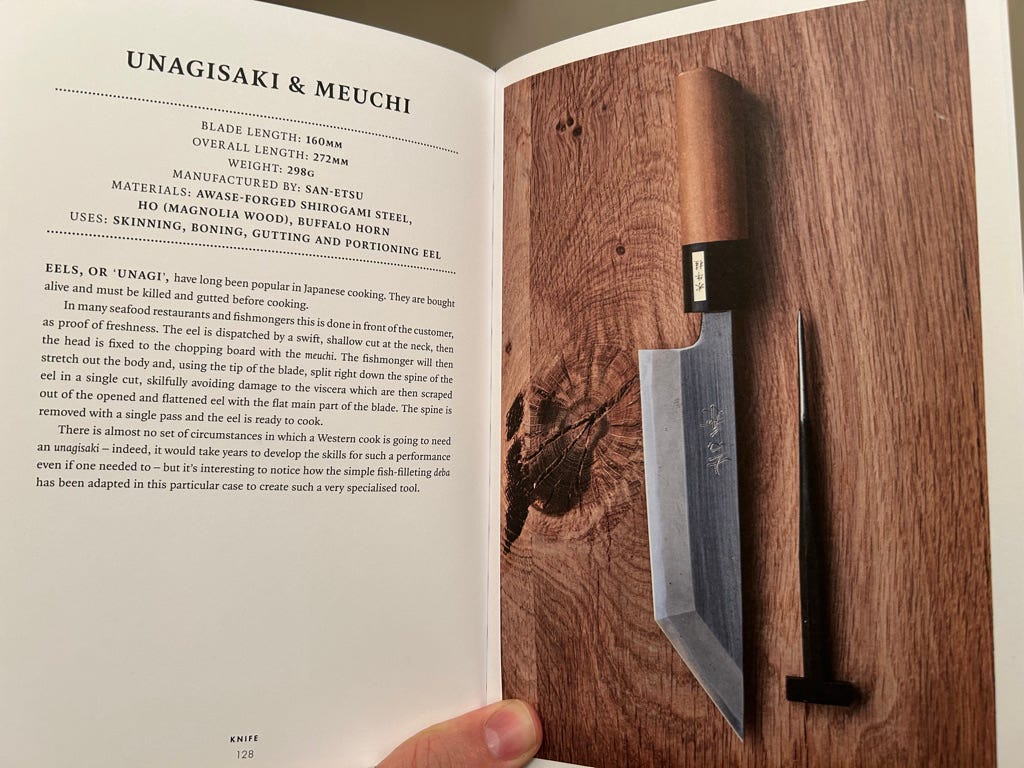

I honestly wasn’t quite prepared for the spectacle, and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t find it a bit intense. I’ll spare you the gory details of the process, but I will mention that in Japan, there’s a specific knife and spike designed solely for this purpose.

The couple next to me noticed the intensity on my face and asked me in broken English, “You eat unagi in your country?” To their surprise, I said yes—though not like this! In fact, it’s quite traditional to eat eel both in the south of Italy (capitone, especially at Christmas in Campania) and in the north, in the Veneto area of the Po Delta. As a matter of fact, my Venetian friend swears they kill eels in exactly the same way over there!

A Master’s Craft

Becoming an unagi chef in Japan is no joke—it’s considered a high culinary art. It’s said that it takes:

3 years to learn to skewer

5 years to learn to grill

A lifetime to master the tare (sauce)

I think by now you’re starting to understand just how special it is to go out for an unagi meal!

This meal was a set menu, and it’s prepared entirely from scratch—meaning the eel they show you alive is the very eel you’ll eat. So yes, it did take a while for the food to be ready. But when it finally arrived, it looked magnificent.

This particular menu featured two styles of eel, layered with rice in a lacquered box: grilled tare-style on top, and steamed eel in the middle. It was accompanied by a clear soup made with the eel’s liver, some pickles (there is no Japanese meal without pickles), a raw egg yolk for dipping (so rich and delicious), and a fresh wasabi root for grating.

Tiny parenthesis here to let you know: most wasabi you get in the Western world isn’t wasabi at all—it’s usually horseradish mixed with mustard powder and food coloring. Real wasabi, like the one in the picture, has a completely different flavor: less pungent, more complex and floral, with an almost sweet undertone. It’s also very expensive, incredibly difficult to grow, and has a short shelf life—which is why it’s so rare outside of Japan. The experience of having your own little wasabi root to grate fresh at the table was almost worth the entire meal by itself.

But of course, the unagi was glorious. The meat was fatty, rich, and incredibly delicate at the same time. The caramelized tare was sweet, with the amazing smell and flavor of the traditional Japanese grill—typically prepared with binchotan, a type of charcoal made from ubame oak, known for its high heat, long burn time, almost no smoke, and very delicate aroma.

Traditionally, unagi is also eaten with sansho pepper, the Japanese cousin of Sichuan pepper. It’s freshly ground (see the little mill in the picture) right over the eel before eating, and its citrusy, numbing heat cuts perfectly through the richness of the meat.

If you are interested in watching the whole process of butchering and preparing unagi, I have found this video online (but don’t say i didn’t warn you).

I should perhaps mention here that after this meal, a friend informed me that eating unagi comes with serious sustainability concerns. I did a bit of research and discovered that the Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) has been classified as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) since 2014, with populations continuing to decline.

Eel farming in Japan relies entirely on wild-caught juvenile eels, known as glass eels, since breeding them in captivity has not yet been achieved on a commercial scale. This dependency on wild populations has led to overfishing and a significant rise in illegal trade—including the poaching and smuggling of glass eels from regions such as Europe and North America to meet demand in East Asia.

In response to this crisis, the Japanese government has introduced measures like the Inland Water Fishery Promotion Act, which mandates permits for eel fishing and farming, and increases penalties for illegal activities related to the eel trade. Japan has also begun projects aimed at improving the traceability of eel products and enhancing stock assessments.

It was a glorious meal and overall an extraordinary experience—but also, probably one I won’t be repeating any time soon, unless the situation significantly improves.

Omakase: on trusting the Artist

One of my favorite things about Japanese eating culture is the concept of Omakase (おまかせ).

This magical word literally means “I leave it up to you,” expressing the idea of letting the chef decide what they will prepare for you. It’s a philosophy that resonates with many things I believe in, especially when it comes to respecting someone’s craft and skill. For me, it’s very much like the way I approach music. When I go to a concert, I choose the performer, but I certainly don’t expect to tell them what I want to hear. Similarly, when I collaborate with an artist, I want them to feel free to express themselves within the realm of my music, rather than being overly precise about what I want.

So, in food—especially high-end cuisine—I pick the restaurant and its chef(s), and then I say, “Please cook what you like and what you think tastes best right now.” Since I’m not particularly picky, I conceive everything that enters my mouth as a sensorial experience. I enjoy the mere fact of flavors and textures and love observing how I experience these things. It doesn’t mean I love everything, but I always appreciate the experience itself. The same goes for music—I enjoy the sensorial and sensuous experience of sound entering my ears; that alone is a pleasure.

Many people associate omakase mostly with sushi. If you missed my sushi chapter, you can check it out below.

How to Sushi-ya

Food in Japan is amazing, that’s a fact, and you probably know about it already since it’s definitely no secret. After 10 days in Japan I can confirm that!

The Art of Frying

In Japan, the idea of omakase applies to many different culinary arts. One I wanted to try on this trip was the high-end tempura omakase. I had expressed this desire early on, and two of my friends took me to Tempura Yama no Ue Roppongi Tokyo Midtown Ten.

The concept of battered and deep-fried food is said to have arrived in Japan with Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century. Even the word tempura seems to connect to the Latin word tempora, referring to times of meat abstinence (giorni di magro in Italian) that I’ve mentioned several times before. As usual, the Japanese took the idea, developed it, refined it, adapted it to local ingredients, and turned it into an art form. So, from simple street food, it became Michelin-star-level cuisine.

I’m sure most of you have experienced tempura in some form, but I want to spend a minute discussing what high-quality tempura really is. In theory, tempura is very simple food. Like sushi, it represents the perfect idea of shokunin—someone who masters a precise craft and refines it little by little every day. Perfectly executed tempura features a very light batter made of cold water and flour (sometimes with egg yolk). The food is only partially covered with batter (as you can see in the pictures below), resulting in a dish that is light and crispy but never oily. It’s not supposed to leave you with the feeling of having eaten heavy fried food.

At a high-end tempura restaurant, the chef uses two pots for frying—one at a higher temperature and one at a lower temperature. You normally sit at a counter directly in front of the chef, who prepares and fries each piece of tempura individually, one at a time, and serves it to you immediately—still sizzling. You get a few condiments like grated daikon, a dipping sauce, and coarse salt. The food is served on a little metal tray to maintain its crispness all around (if it rested on a plate, the steam would make the bottom soggy very quickly).

In general, a tempura tasting menu features a progression of individual seasonal pieces, moving from lighter items to richer and more flavorful ingredients. Edo-style tempura (Tokyo style) usually emphasizes seafood. Our omakase meal began with ebi (shrimp), served in two different ways: first the heads, which were crunchy and full of flavor, followed by the rest of the shrimp. Many people in Asia—especially in Japan—also eat the tail end of the shrimp. When properly cooked, it has a nice crunchy, crisp texture and an almost sweet flavor.

I didn’t take pictures of everything that was served, but here is a selection of the vegetables and mushrooms (pic 2). The aubergine (pic 1) was incredibly soft and delicate, and the carrot was one of the tastiest items on the menu, with perfect texture and a very sweet flavor. I was told that these vegetables are first fried raw in the lower-temperature oil, then moved to the higher-temperature oil to achieve their crispness.

Below, on the left, is a beautiful piece of sea bream, and on the right, the final tendon course. In this case, it was a bowl of rice topped with conger eel tempura, drizzled with tare sauce, accompanied by some pickles and a miso soup.

It was a beautiful meal and felt surprisingly light, especially considering it was made entirely of deep-fried foods.

A few tempura notions in this short video

I always used to say that nobody can fry like the Neapolitans (because of their skill and traditions), but now I’m gonna have to change my motto to “nobody can fry like the Japanese”. Once again the Japanese have proven that when it comes to learning a technique and improving it to perfection, they have no competition…

To be Continued

More Japan adventures coming soon, stick with me as I will venture into the fantastic world of Kaiseki cuisine.

If you enjoy these posts and want to learn more about my explorations through food and music, please consider becoming a free or a paid subscriber to “Cooking by ear”.

Thank you for sharing your transcending dining experiences in Japan! I am also glad you’ve mentioned about the sustainability concerns about Unagi( and other species that we are diminishing). May we find a balance between art, nourishment, and Mother Nature.

Ooh I'm SOOO jealous - Takahashiya!

And I want that unagisaki! Never mind that I'll never use it for its actual mission in life 😂.