People ask me often how I feel about eating vegetarian food, knowing that I eat meat and fish.

What a strange question to ask…

I am not sure why there is an assumption that if you eat fish and meat that’s all you want to eat all the time for every meal!

I honestly feel great about eating vegetarian food and I love good vegetarian food. I grew up in a household where meat was eaten once or twice a week (fish at least twice) and in my own home we try to eat meat at weekends only.

I am not very fond of vegetarian food pretending to be meat (like fake burgers etc…) but I understand and respect the function that it has for many people who try to be vegetarians. Ultimately I think that if you dig and research a bit, you will find out that there are so many cultures with incredible vegetarian food traditions that are very tasty and not pretending to be something else other than vegetables.

When I moved away from Italy in the late 90’s I often heard (from non Italian vegetarian friends) that Italy was an amazing place to visit if you are vegetarian.

I somehow never thought about it in those terms, but back then many European countries such as Spain and France still struggled with serving vegetarian food which was not just the side dishes for a piece of meat or fish.

I guess it’s true that in Italy we have a long tradition of vegetarian dishes, probably heritage of being a very poor country until the second half of the 20th century.

Food historian Alberto Grandi often says that most Italians had a diet based on legumes (in the south) and polenta (in the north) well until the 1960’s.

The millions of Italians that emigrated in the 19th centuries towards the Americas were incredibly poor and literally starving. Access to meat was a sign of wealth for poor Italians and I think it’s no coincidence that Italian American food has become so meat-heavy.

Going back only two generations, most Italian people ate meat quite rarely, especially in the south. My Nonna (she was born in 1918) ate meat a handful of times in one year and usually these times were associated with big religious festivities.

Meat was mostly consumed in stews in which cheaper cuts were cooked together with vegetables for a long time to become less tough and to infuse the minestra with some meaty flavour.

Poultry was definitely more common than red meats and, even in rural areas, owning a pig was a sign of relative wealth. When the pig was slaughtered by a professional itinerant butcher (Norcino), the various products like hams, sausages, blood sausages, salami, soppressate would last a family for a year.

The lack of proper refrigeration made fish also quite hard to get unless you lived on the sea and were connected to fishermen.

Religion and more specifically the Catholic church might be the other reason for the Italian vegetarian heritage, and especially the “mangiar di magro” tradition.

In case you are not familiar with this concept, for centuries the Catholic Church imposed that for a number of days of the year you should eat di magro.

The concept of mangiare di magro (lean) as opposed to mangiare di grasso (fat) changed slightly over time. From the middle ages onwards it meant that for a specific amount of days during the year, you were not allowed to eat any type of meat, any animal fat (lard and butter) and any type of milk derived products (cheese) and no eggs.

Fish was allowed and that’s the main difference to what we would call veganism nowadays. I also want to mention here that the cheapest and most common fat for cooking among the normal population was lard well until my grandmother’s generation. Butter was more common in the north, but still a sign of wealth, and going against the myth of the completely fabricated concept of “Mediterranean diet”, oil was not cheap and not commonly consumed everyday (a story for another day!).

The idea of fasting is certainly very old and common to many religions and it was part of the Catholic Church from its earliest days. At first Christianity inherited some of the food prohibitions of Judaism (pork, rabbit, hare) but later dismissed them and settled into the concept of “parsimony”. The Catholic church in fact didn’t impose fasting per se, but insisted on frugality and simplicity of food in the magro days.

By the middle ages the days in which you were religiously and legally obliged to eat di magro were nearly 1/3rd of the year. Usually the weekly days for magro eating were Friday and/or Saturday, and there were other longer periods like lent and other pre-religious festivities. During these days butchers were not allowed to sell meat and breaking these rules could result in serious punishment and even death sentence!

Fasting has always been a spiritual core belief behind many religions. When it comes to Christianity let’s not fall into the trap of thinking that the Catholic church was imposing these rules for ethical respect of animal life, or for health or sustainability reasons.

Isidoro from Sevilla, a 7th century bishop makes it pretty clear:

Le carni non sono proibite in quanto cattive ma perché il loro consumo genera la lussuria della carne.

Meats are not prohibited because they are bad per se, but because their consumption generates lust (of the flesh).

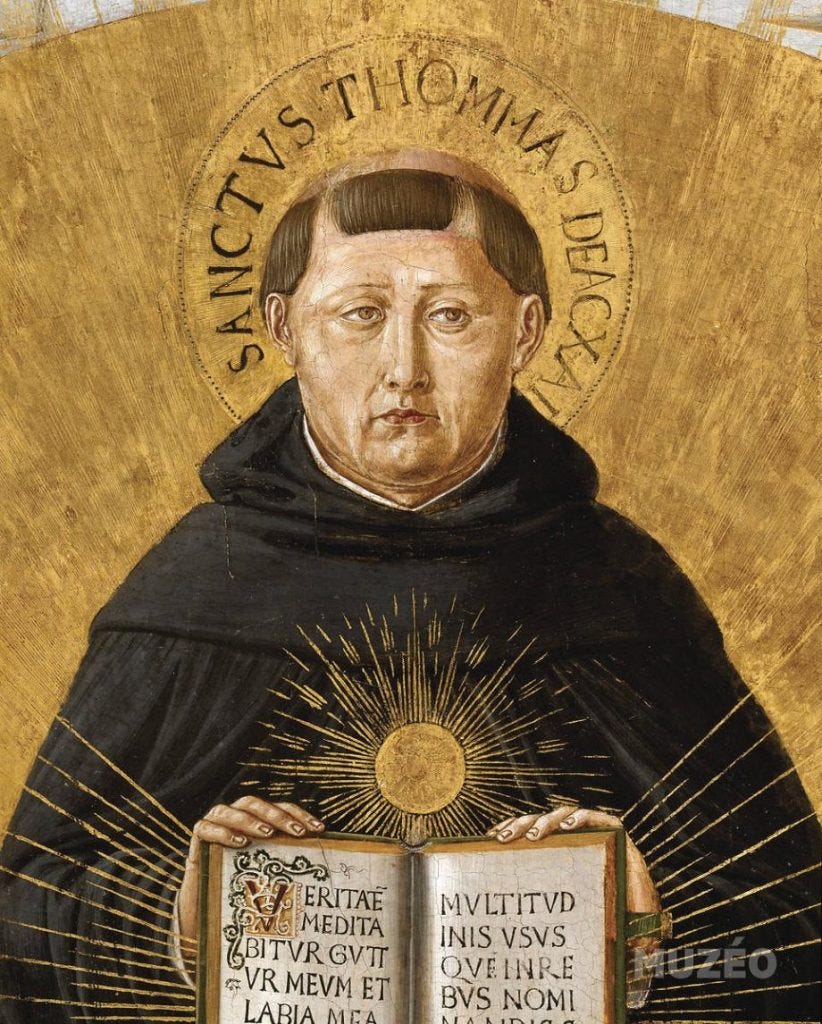

In the 13th century saint Tommaso d’ Aquino said:

Il digiuno è stato istituito dalla Chiesa per reprimere la brama dei piaceri del toccare, che hanno per oggetto il cibo e la voluttà. L’astinenza deve dunque riferirsi agli alimenti più dilettevoli e più eccitanti; questi sono la carne dei quadrupedi e degli uccelli, come anche i prodotti del latte e le uova».

Fasting has been established by the church to repress the pleasures of the “touch”, which manifests itself with food and sensual pleasures. Abstinence has to be referred to the most delightful and exciting foods, such as the meat of quadrupeds (four legged animals) and birds, as much as milk products and eggs.

So to make it very clear, eating meat was a pleasure comparable to sex and therefore sinful in principle and inducing to gluttony and to sins of the flesh.

Saint Benedict, founder of the Benedictine order went as far as imposing the magro diet permanently for the monks of his order. His monks were not allowed to eat meat unless they were sick. The definition of quadrupeds created a never ending debate when it came to ducks, beavers and other animals tied to water, as many tried to make them pass for fish so that they would be allowed to eat them.

In the 14th century Pierre Bohier, a monk from the Languedoc region, describes a recipe with finely chopped meat used as stuffing as something possible to eat, as the process of mincing alters the quality of the food…I guess those monks were dying to find a subterfuge to be allowed to eat some form of meat!

The general diatribe of magro eating seems to have been at the core of the reformation started by Luther, to which the counterreformation answered with even more severe restrictions and rules on grasso and magro eating. This difference remained one of the defining distinctions between Catholics and Protestants for centuries to come.

Fasting and observing the magro diet is still one of the 5 precepts of the Catholic church and should be observed from age 14 to 60

You shall attend Mass on Sundays and holy days of obligation.

You shall confess your sins at least once a year.

You shall humbly receive your Creator in Holy Communion at least during the Easter season.

You shall keep holy the holy days of obligation.

You shall observe the prescribed days of fasting and abstinence.

In practical terms it is very curious to see how most historical Italian cookbooks have recipes that are adaptable for magro eating days.

In the Liber de coquina (13th century) a recipe of breaded chicken breasts fried in lard is adapted to giorni di magro with this sentence:

“e nei giorni di digiuno si faccia con olio ... e si ponga pesce”

in fasting days you can make this with oil…and use fish.

There are plenty examples of such substitutions but the ones that are the most interesting are the contrafacta recipes, i.e. the recipes that try to replicated an existing animal product but using a magro based alternative.

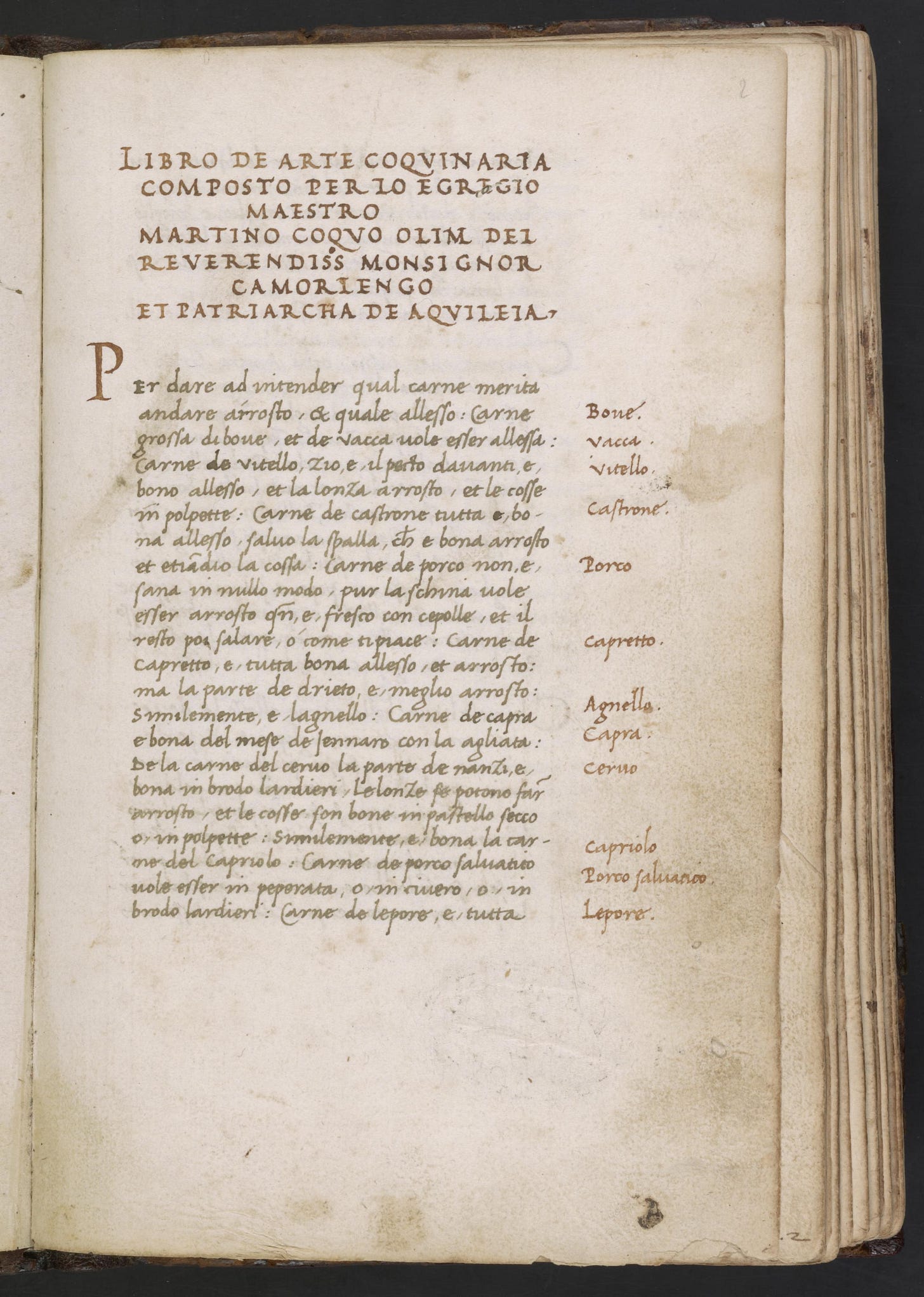

In the Libro de arte coquinaria, Maestro Martino da Como (second half of the 15th century) comes up with ova contrafacte in Quadragesima. In this elaborate recipe he cooks rice in almond milk with wheat starch, he strains it, adds fish stock and sugar and colours it with saffron to create something that looks like hard boiled egg yolks!

In another recipe he creates cheese from almond milk and fish stock.

In a way this is the same concept as creating those plant based hamburgers and chicken nuggets that are so popular today!

Whether this is a plausible reason for the many vegetarian and vegan dishes in the Italian culinary heritage, it is interesting to dig into this history and to discover how it has shaped taste and traditions. Obviously most magro recipes use fish so they are not vegetarian, but I believe that these rules combined with the scarcity of fish and meat created many of these traditions.

In the coming months I will share some of these vegetarian legume based dishes that my mother and my aunts cooked for me when I was a child, starting from the pasta e ceci (pasta with chickpeas) that I posted about a couple of weeks ago…stay tuned.

What a comprehensive, detailed, well-thought-out and delightful read this article has been! Almost like listening to a good song... you want to go back to the start and do it all over again! Thank you so much for the great ten minutes of reading in a slow, savoring manner! I gave up animal-based meals twenty years ago, but I've never made it "political" (or polemical) as I would not be happy if someone told ME how to eat. I already knew about most of the reasons why Italy (and Greece as well) had so many and diverse non-meat dishes, but I've never had the chance to interchange with someone about it that has grown up in those places and can speak from experience, nor did I know any details pertaining to terminology, historical timelines and more. Your wonderfully researched and presented write-up has been a fun ride into history and food.

PS: I also love how you raise up other interesting topics in many of your posts using "but that is a story for another day." I will be pleased to wait for whenever one of those days occurs.

Carry on, carry on, what a pleasure to observe a person talented and well-rounded and authentic in our crazy, high-jacked world. You (and your partner, ha ha) are the proverbial "breath of fresh air." I want you to know that there are many of us out here who truly appreciate your time and hard work communicating with all of us.

This is not only molto interessante in its own right, but hits home today as we just returned from two splendid weeks in Italy (Florence, central Umbria, Rome) eating both magro and grasso style (though without access to those terms during our trip!), and marveling at the care invested in cooking at every level, locality, and occasion. We also cooked a bit on our own and thrilled to the quality of ingredients available in the local stores and supermarkets. I am so enjoying your food commentaries (and your music of course!).