The OG tasting menu

Exploring the Art of Kaiseki Dining and the Timeless Tradition of Japanese Hot Springs

For my recent trip to Japan, I had made a list of culinary adventures I wanted to have, and one of them was to experience the art of Kaiseki. I was a little worried, though, as kaiseki meals are usually very expensive and often served in exclusive restaurants that are hard to book—especially for foreigners.

The Art of Kaiseki Dining

In case you're not familiar with the concept of kaiseki, today it represents the pinnacle of the multicourse tasting menu. It is known for its refined aesthetics, use of local and seasonal ingredients, and strong emphasis on balance, harmony, and presentation. But historically, kaiseki originated as simple, humble meals served during the Japanese tea ceremony in the 16th century. The term 懐石 (kaiseki) literally means “stone in the bosom,” referring to the Zen monks’ practice of tucking a warm stone into their robes to ward off hunger. The food was modest, seasonal, and meditative—intended to prepare the body and spirit for drinking matcha.

It’s only by the Edo period (1603–1868) that kaiseki became associated with luxurious multi-course meals served at restaurants. Over time, the two styles began to blend, and the more elaborate form of kaiseki evolved into what we associate today with fine Japanese dining.

The concepts of seasonality and the use of local ingredients, minimal aesthetics and presentation, respect for ritual and experience, and the structured progression of the menu have deeply influenced fine dining cuisine in the Western world—so much so that you could consider kaiseki the original inspiration for most contemporary tasting menus.

A typical kaiseki meal includes a progression of small, beautifully presented dishes such as:

Sakizuke (先附): an appetizer, like an amuse-bouche

Suimono (吸い物): a clear soup

Sashimi (造り): sliced raw fish

Yakimono (焼き物): a grilled course

Nimono (煮物): a simmered dish

Agemono (揚げ物): a deep-fried dish

Mushimono (蒸し物): a steamed course

Shokuji (食事): rice, miso soup, and pickles

Mizumono (水物): dessert, often fruit or wagashi (traditional sweet confections)

Experiencing Kaiseki at a Onsen.

One of the most exciting ways to experience a kaiseki meal is to spend a night at a fancy onsen. An onsen (温泉) is a Japanese hot spring, and by extension, refers to the bathing facilities and traditional inns (ryokan) built around them. As you might know, Japan is a volcanically active archipelago, and natural onsen are found all over the country. Most traditional onsen tap into geothermal sources, and the water comes out naturally heated and mineral-rich—often with specific health and skin benefits.

While I was visiting Tokyo, two Japanese friends asked if I wanted to join them for a night at a fancy onsen. I was initially a little reluctant, as I was focused on my culinary Tokyo experiences, but everyone I spoke to insisted that visiting Japan without experiencing an onsen would be something to regret forever.

One of the most popular spots for onsen in the Tokyo area is Hakone, in Kanagawa Prefecture, about 1.5 hours south of Tokyo. So we traveled south and spent the night at the beautiful and luxurious Hakone Suishoen.

As you arrive at the facility in the afternoon, everyone is provided with traditional clothes to wear while staying at the onsen:

Yukata (浴衣): a casual cotton kimono, to be worn after bathing, to dinner, and in all public spaces

Tabi (足袋): traditional Japanese socks that separate the big toe from the others

Geta or Zori (下駄 / 草履): traditional wooden or straw slip-on sandals for walking to and from the bath

The main reason you go to an onsen is to soak in thermal waters, but traditionally it's also a place where people go to wash themselves. Next to the actual pools of hot water, there are small washing stations with showers, and toiletries are usually provided.

Traditionally, people enter these hot pools completely naked—something that might feel a bit strange, especially considering how reserved Japanese culture tends to be regarding personal space and physical contact. Each onsen has separate, divided areas for men and women.

Another thing to note: tattoos are not allowed in the majority of onsen. This is because, historically, tattoos in Japan have been closely linked to the yakuza, Japan’s mafia. As a result, tattoos came to symbolize criminality and intimidation. Younger generations in Japan are more accepting of tattoos as fashion or personal expression, and with the rising number of foreign tourists, more onsen are becoming tattoo-friendly—especially in cities and tourist-heavy regions (but do check before you go!).

But back to the food. One of the main reasons I was here was that high-end onsen often feature amazing restaurants serving kaiseki-style meals. Sometimes, you're served dinner in your room, but at this particular place, they had a proper restaurant with small, individual, beautifully designed private rooms.

The Feast

After spending an hour relaxing in the hot bath and showering, we got ready for dinner. Our private dining room featured a traditional low table called a horigotatsu . A horigotatsu has a sunken floor beneath the table, allowing people to sit comfortably with their legs hanging down—similar to sitting in a chair—while still giving the appearance of sitting on the floor. This design combines the coziness of traditional Japanese seating with the comfort of Western-style legroom. The table also had a blanket to cover your legs and was heated underneath.

The dinner itself was incredible—every single dish was beautiful and presented in the most exquisite ceramic ware. In a kaiseki menu, presentation is just as important as flavor, and it changes with the seasons. Since it was the beginning of spring, the meal was an explosion of colors, reflected not only in the ingredients but also in the careful selection of bowls and plates.

After this glorious and beautiful meal (I think a few tears may have been spotted rolling gently down my cheeks while eating some of that tuna sashimi), we retired to the room. I slept on a beautiful futon with the window slightly open and the sound of a small river just outside.

A futon (布団) in Japan is a traditional bedding set laid directly on the tatami floor (woven straw mats). It’s laid out in the evening for sleeping and then folded and stored in a closet or cupboard during the day, keeping the room multipurpose.

The next morning, I woke up early and spent more time in the baths before we headed to the restaurant for breakfast—an equally exciting meal at these types of establishments. It had actually been a very cold night, and we discovered that it had snowed, which is quite unusual for March!

The breakfast featured individual wooden boxes with an assortment of many small dishes centered around a traditional Japanese breakfast. There was a beautiful piece of grilled fish, a perfectly made Japanese omelette (tamagoyaki), a soup, vegetables, pickles, and some marinated fish roe. One dish I had never tried before was very fresh dressed tofu (pic. 1), which was light and delicious—almost like a custard in both appearance and texture!

It was indeed an amazing experience, and now I can clearly see it as one of the best quick two-day getaways I could possibly imagine. Hard to beat spending a night in a beautiful room surrounded by nature, soaking in warm thermal waters, and enjoying two incredible meals. It’s definitely not a cheap affair, but the quality and level of hospitality were incredibly high.

Hospitality and Overtourism

While at the onsen, I was chatting with my friends, and Yurie lamented that she wouldn’t be able to bring me to her favorite restaurant in Tokyo. When I mentioned I’d be in Tokyo on my own for my last day before returning to Ireland, she said she could try to book me a place. I got excited at the thought but knew this was a high-end kaiseki restaurant, and places like that usually can’t be booked just a couple of days in advance. Nevertheless, she seemed confident she could get me a counter seat (the best spot, if you ask me!) on just two days’ notice. She called, and two minutes later I had a reservation for lunch.

I was incredibly excited—until trouble arose. When the person she was speaking to realized the booking wasn’t for Yurie but for a foreigner, the tone of the conversation changed immediately. They didn’t want to take the booking anymore, saying tourists often cancel on them or don’t behave properly, and in a place like that, they can’t afford no-shows. Apparently, this has become a problem recently in Japan due to overtourism…and, I daresay, a certain type of tourism. Some places are starting to shut down to foreigners, and some restaurants don’t accept people who don’t speak Japanese. It’s a controversial stance, sparking conversations about racism and discrimination.

My friend actually got quite upset by this incident and kept insisting on the phone that she would vouch for me, even offering her credit card details. She kept saying the reason I was in Japan was for the food—meanwhile, I was on the other side of the room screaming, “Tell them that unless I die, I will be there on Saturday!” The back and forth went on for a while until my friend asked to speak to the manager. The manager called her back and was actually quite apologetic, especially after realizing that Yurie and her family had been regular clients for a long time. In the end, she managed to get me a reservation at the famous Kikunoi restaurant.

As you can imagine, given this preamble, I was a little nervous to show up for this meal, so I arrived 30 minutes early (being late is not tolerated in Japanese culture, and that’s actually fine with me!). This is generally good advice, since it’s often not easy to find restaurant entrances and locations in Japan, and addresses can be quite enigmatic. Everything went smoothly, and honestly, I was treated like a king.

I started from a place of respect, though—I was well prepared on how to behave and on the significance of the food I was about to receive. I knew how to express my gratitude and appreciation in Japanese, and I even showed up in my tabi socks (in these kinds of places, you have to remove your shoes to sit at the low counter). I also think the chef who served me noticed how moved I was by the food, which helped create a connection. So much so that, in the end, he followed me out and kept bowing as I walked down the street—and insisted I take an umbrella to take home since it was drizzling.

Japanese hospitality is honestly incredible, deeply embedded in the culture, and some of the best I have ever experienced. So if Japan shuts down to foreigners, you have to ask yourself a few questions: Why do we as tourists always expect things to be our way? We expect to speak our language and be treated as we would at home. But traveling should be a humbling experience—you should arrive open-minded and ready to absorb other ways of doing things. This is the whole point of experiencing different cultures.

Japan can be misleading because it is the richest capitalist country in East Asia, so it’s easy to think it’s similar to the Western world. But its history and traditions come from a very different place and are still present in everyday life, even in Tokyo. It’s a place where respect, quietness, and being unnoticed are very important, so it’s incredibly easy to go wrong.

Other than the booking incident, I had only the best experiences in Japan when it came to hospitality. But it always started from a place of respect and research on my part. Needless to say, I mostly traveled alone, was well prepared on Japanese food, and had learned as much Japanese as I could to express my gratitude and appreciation. I also always asked people if it was okay before doing even the most obvious things, such as taking pictures of food and chefs.

Having said that, I don’t want to sound naive—I’m also aware of Japan’s complex history and its past and present issues regarding colonialism, racism, and sexism. It has been closed to the outside world for a very long time (and still is, to some extent), so I think it’s a conversation full of subtle shades.

High-End Kaiseki in Tokyo: The Kikunoi Experience

But back to the food—because this ended up being one of the most amazing culinary experiences I have ever had. Kikunoi (菊乃井) is one of Japan’s most iconic and revered kaiseki restaurants, created by chef Yoshihiro Murata, a third-generation kaiseki chef and one of the most influential figures in modern Japanese gastronomy. The main restaurant is in Kyoto (*** Michelin stars), with a Tokyo branch in Akasaka—the place I visited (** Michelin stars).

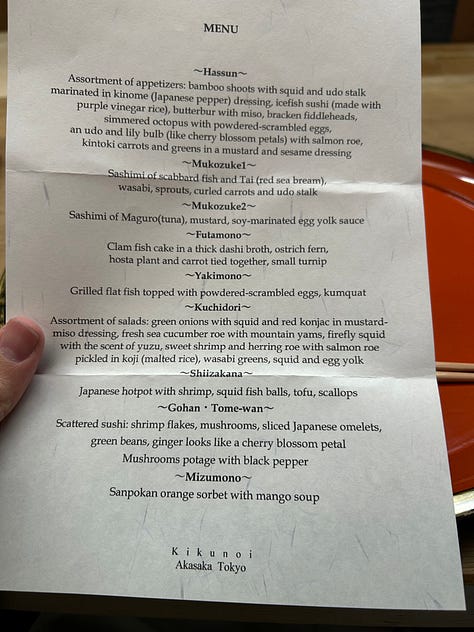

Kikunoi's cuisine is deeply rooted in seasonal rhythms, aesthetics, and tea ceremony traditions. The March menu was inspired by the Hinamatsuri (Doll’s Festival).

You can see in the menu above the full Kaiseki sequence presented here, featuring all the dishes served to me.

Below are the first three courses, where the tuna sashimi with mustard dipped in soy-marinated egg yolk was possibly one of the tastiest things that have ever entered my mouth (and yes, tears were shed… extraordinary tuna seems to do this to me, maybe because of my family’s Sicilian tuna connection). I’d also like you to notice the beauty of the porcelain and the presentation of each individual dish, no matter how small. Every microscopic detail was carefully planned and executed, both in presentation and in the actual taste when eaten.

The Futamono was a clam fish cake served in a dashi broth, so beautifully presented that I almost didn’t want to eat it (who knew you could eat fern?). The Yakimono was a masterpiece in itself—a piece of white fish grilled on binchotan charcoal right in front of me, topped with powdered egg yolk to resemble a mimosa flower and accompanied by a sour kumquat.

All the small “salads” presented in tiny dishes were delights of flavor, texture, and aesthetics—beautiful worlds unto themselves (see pic 1 below). The final rice dish (pic 3) was a super fancy version of chirashi zushi (scattered sushi), accompanied by a rich, thick, and incredibly flavorful French-inspired mushroom potage soup. Dessert, usually very light in Japanese cuisine, was a fresh citrus sorbet served in a mango soup. It didn’t look very exciting compared to the rest, but it was incredibly refreshing after such an amazing feast for both the taste buds and the eyes.

I honestly don’t have enough words to describe this meal. It felt like a meditation—a spiritual experience for me. I was alone (my preferred way to visit high-end restaurants) and completely lost in the food and the moment. Everything was perfect: the pace, the service, the flavors, the temperature and texture contrasts. The technical mastery and precision of execution were truly impressive, yet nothing felt showy or contrived. It was all about harmonious flow, balance, and structure. The beauty of the microscopic details served the overall organic structure of the meal.

I should also mention that this meal cost about 100 euros, excluding drinks, which is quite affordable compared to what an equivalent two-star Michelin meal would cost anywhere else at this level of cuisine. This was the price for lunch—and as I mentioned earlier, meals in Japan are much cheaper at lunchtime than dinner. And by that, I don’t mean a reduced lunch menu like you often see in Europe or the US—it’s actually the same menu served at dinner, just at a much lower price.

So, if I may offer one piece of advice: while in Japan, always choose your fancy meals at lunchtime to save a lot of money. Also, if you want to try booking high-end restaurants like this one, use a concierge service from your hotel. Alternatively, you can use the very popular (and truly amazing) Tabelog website, but bear in mind that not all high-end restaurants are listed there.

If you enjoyed learning about Kaiseki and Onsen, please consider signing up as a free or paid subscriber to “Cooking by Ear.”

Fabulous post Francesco! Wow. I actually devoured every word having visited Japan shortly after you did. It brought back so many great memories of that trip. Unfortunately we did not visit any of the restaurants you mentioned however, our culinary experiences were excellent. The presentation of the meals was flawless. The freshness of the fish unforgettable. The customs and the kindness of the Japanese people are calling me back. I will go back again. I’m hooked!

"... traveling should be a humbling experience—you should arrive open-minded and ready to absorb other ways of doing things. This is the whole point of experiencing different cultures."

Absolutely! Open yourself, humble yourself before the amazing variety of ways that human beings interact with each other and with the environment. Soak in the experience without "thinking" stuff and comparing things, and predicting what is what and why it is or isn't! Be ALIVE. Soak it in, your judgment function in the pre-frontal cortex WILL BE THERE WAITING FOR YOU AFTERWARD.

So thrilled you had such a high-moment jewel of a dining experience!